B O D Y | Interview with L’nu interdisciplinary artist

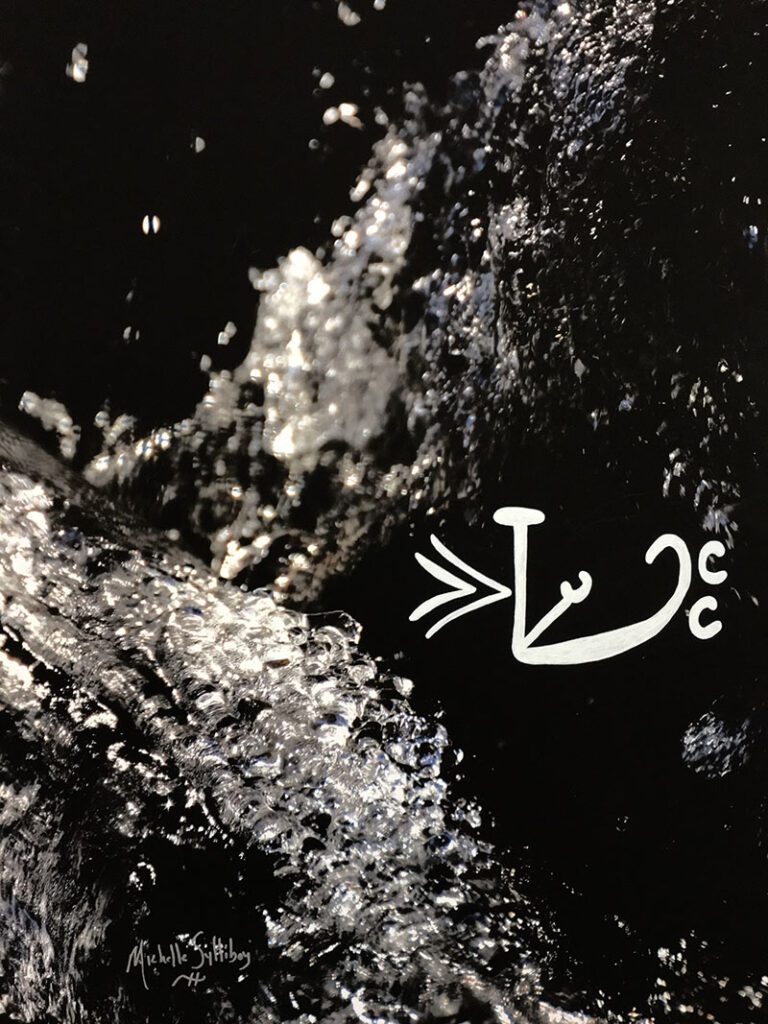

Award-winning author and interdisciplinary artist Michelle Sylliboy (Mi’kmaq/L’nu) was born in Boston, Massachusetts, and raised on her traditional L’nuk territory in We’koqmaq, Cape Breton. Her published collection of photographs and L’nuk hieroglyphic poetry, Kiskajeyi—I Am Ready, won the 2020 Indigenous Voices Award. In 2021, she received the Indigenous Artist Recognition Award from Arts Nova Scotia. In 2022, she was long-listed for the Sobey Art Award. As a PhD candidate in Simon Fraser University’s Philosophy of Education program, she focuses on the artistic promotion of her original written Komqwejwi’kasikl language, and she works as an assistant professor at StFX University in the Education and Art departments.

B O D Y: You’re currently working on your PhD thesis in Education. How did collaborating with others come to form a core part of your art practice, as well as integral part of your dissertation?

Michelle Sylliboy: It started in the nineties when I was organizing poetry readings, and it just became part of my art practice. And that’s something that I wanted to integrate into this dissertation process, because I wanted to be able to involve people and get feedback from anyone that was interested in learning the Komqwejwi’kasikl language. And so, it was easy for me to be in that place of collaboration, because I have been training myself for years. I enjoy it because you learn a lot more when you collaborate and when you share the stage. I’ve always felt that it was important for me to share venues and support artists in whatever capacity. It’s always about supporting artists.

B O D Y: Your dissertation will incorporate multiple mediums. Can you tell me more about this?

Michelle Sylliboy: Yes, well, with the many projects that I did for this dissertation I initially thought about collaborating with musicians. I wanted to play around with sensory input because I know that for me to capture an audience, especially when you’re dealing with a language that is visual and auditory, the best way as an educator is to use multiple modalities like sound and speech and the visual all at once. Then whoever’s in the audience, it didn’t matter what their learning styles were. They were going to be able to follow along at that moment. With music, they feel the music, they hear the poetry, but they visually see something that is actively going on at the same time. And now, I have their attention and they walk away with this feeling of having learned something.

B O D Y: So, through collaboration, you create a multi-sensorial learning experience.

Michelle Sylliboy: Yes, because I knew that from having collaborated with musicians when I lived in Vancouver, I recognized the value and the power behind music. Music and poetry go together. They’re linked, they’re married, they’ll be married for centuries. And so, I wanted those two mediums to express as one and to reach the audience – something I couldn’t do just by reading poetry. And I was able to work with people that had a different way of working with their craft. I was lucky I had an opportunity to work with violinists, saxophone players, pianists, and percussionists. I’ve had all kinds of vocalists. When I did a collaboration in Vancouver, I had an a cappella group called M’Girl and I had a quartet – a pianist, a cellist, a percussionist? No, it was a trio – a pianist, violinist, and a cellist, along with the a cappella group. And so that combination of aural sensations was magical. It was the only concert I didn’t record. And it was probably one of the best because it had the element of indigenous vocal sounds, of four women, vocalizing as they listened to the instruments and the instruments listening to the vocalists, but they were all paying attention to my reading. And then involving the audience to draw the Komqwejwi’kasikl (the suckerfish writing) live so that they had a sense of belonging and the experience of being part of the performance. A performance allows you to have an interactive relationship with your audience. That was important for me. I wanted to be inclusive and by including them, they walk away with the sense they were part of something, and they learned something. They’ll leave wanting to know more and you want that. You want them to go out and say, okay, I want to know more. I just got entertained, but I also got an education.

B O D Y: You collaborate often with settlers. Can you tell me more about this?

Michelle Sylliboy: I never thought about just collaborating with just settlers. I collaborate with others as well. I collaborate with artists.

B O D Y: Okay, so it’s really about who your collaborators are as artists.

Michelle Sylliboy: Yes. And it just so happened that in the last several years I’ve collaborated with quite a few settlers, and other people of colour. I invited L’nuk artists to respond to the language, but it wasn’t really a collaboration, it was more about sharing the exhibition stage of the gallery space and to look at the language from different L’nuk perspectives. It was for a group exhibition at the Cape Breton Center for Craft and Design, Alan Syliboy does paintings of petroglyphs and I invited Loretta Gould to respond as a painter. They have unique perspectives from the same nation who promote the language on different levels.

B O D Y: So, your collaborations are educational for the audience and the artists you collaborate with – particularly settlers.

Michelle Sylliboy: Yeah. When the language was originally published, our own Indigenous Mi’kmaw narrative was removed from that history, the origins of the language. And so, it was very important for me to do projects from an L’nuk perspective and to reclaim the narrative around where the language comes from because we were never given that title. My elder, Lillian B. Marshall, before she passed away made a statement through social media, it was on a Facebook wall. She was very proud of my work. She was my mother’s best friend in the early sixties, in Boston. And she said to me, Michelle, you make sure you let them know that we’ve always had this language. And that statement conveyed an infinite timeline. She didn’t say, you know, we’ve only had this language when the priest published. It was much longer than that, thousands of years of language and culture, and to acknowledge that was my mission. Grand chief, Gabriel Sylliboy, would write documents using the Komqwejwi’kasikl, and he no doubt taught his grandchildren how to read and write using the Komqwejwi’kasikl. And so, all of this is a rich history. When I started to do the work, I wanted to make sure that settlers knew that we’ve had this language much longer than the so-called historical documents of what the priest Christian Le Clerc wrote in his autobiography. And so, the first time I did a major performance, (I guess it would be a performance at Lumiere in Sydney), they invited me to share the language by setting up a touch screen. The tech department bought a massive projector to project onto this massive wall. I was excited as they were about sharing the language. I had all the dictionaries set up on the table. People looked for a message and then they drew it on a huge touch screen. I felt like a Disneyland attraction because I had the biggest lineup of people wanting to draw – children and adults.

B O D Y: To draw the hieroglyphs?

Michelle Sylliboy: Yeah. Many of them, 99% of them didn’t know we had a written language. And at that moment, (and that was like in the early part of my fieldwork), I knew that I had to continue that educational trajectory of letting people know that we’re more than just people who lived on this land. We’ve had a rich history of language and song and stories and culture. I use that as part of my guide towards every project that I do.

B O D Y: For this interactive performance piece, would the live-drawn hieroglyph be projected on the screen?

Michelle Sylliboy: Yes, whatever was drawn, people in the audience could see it on the massive wall. That experience inspired me to do performances. When I did my first book launch and exhibition, I didn’t do a performance, but I did it at the second book launch in Halifax where I invited Scott Macmillan and Lindsay Dobbin to do the music together. And it was an interesting mix of music because Lindsay is a professional improviser and Scott Macmillan is classically trained and a composer who performs in jazz, but he says that in the jazz world, they don’t consider him a traditional jazz composer because he pushes the boundaries, and because he pushes the boundaries, I wanted him to collaborate with someone – a younger artist. One of the goals was to bring younger artists next to professional artists or at least, artists that might have an opportunity to collaborate again after the initial meeting. And so, with that kind of collaboration and networking and creating relationships, the networking just blossoms. I had a book launch in Newfoundland. The percussionist was very excited because he always wanted to improvise with his drums and had never done it live, but in his mind. It was an exciting moment because suddenly, somebody said, play with your instrument, have fun with it, and work with your instrument. The saxophone player was also the curator, and then me; all doing this dance. Everybody’s doing a dance. They’re listening to me, but they’re responding, improvising, and creating new music on the fly, which was brilliant.

B O D Y: Wow

Michelle Sylliboy: Yeah, it was beautiful. The saxophone player, Hannah Morgan, is brilliant. She also curated my exhibition and wrote about the exhibit. The first time I did a much bigger performance was after doing my launch in Halifax, at the OBEY Festival. I was the keynote performer. That’s when I invited several musicians to collaborate. I had a pianist, a percussionist, and a synthesizer player. Nick Dourado, Lindsay Dobbin, and Johnny Spence collaborated with me at that event. Now that was a very beautiful performance because it was the first time, I collaborated with incredible musicians who were professional improvisers at the same time. It was mind blowing really because they were able to focus on what they felt during the reading and really pay attention to their instruments regardless. Lindsay, the percussionist, mentioned she can create whale sounds with her drums, so we brought in my whale onto the stage. That was something.

B O D Y: Your whale – the whale sculptures?

Michelle Sylliboy: No, a vertebra. And we called it Billy – the fifth Beatle, Billy the Whale.

B O D Y: So, it was a giant whale vertebra.

Live at Obey Convention 2019 | Michelle Sylliboy and Friends (bandcamp.com)

Michelle Sylliboy: Yeah. In the middle of the stage because I wanted to honor the whale bones that I had done, but there was no place to do that. So, we video projected the image of the whale bones I did and in the middle of the stage the vertebrae represented the whales that I had been working with.

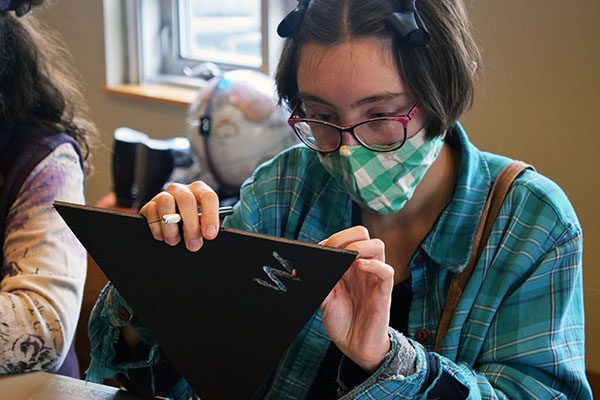

B O D Y: You have an interactive sculptural project debuting this October with Nocturne festival in Halifax. The sculptures are based on a series of light boxes that were created during a workshop you organized on the Komqwejwi’kasikl dictionary for festival Antigonight, in 2021. Do you feel this work is collaborative?

Michelle Sylliboy: Yeah, when we did that project for Antigonight, I didn’t recognize what the light boxes could be when the show ended. I mean, let’s go back to the beginning when the light boxes were created by the community for the performance that you curated. I had the audience think about the residential school children that were being found across Canada. And at that time Kamloops had found 215. And so, I wanted to ask people to think about those children and send a message to them using the Komqwejwi’kasikl dictionary. They cut out their messages for the children and made rectangular cardboard light boxes.

When I brought them home after the performance…nobody took the light boxes with them, so I brought it home. I wouldn’t have brought them home if it wasn’t for animator Leigh Gillam. Because Leigh said, Michelle, this is another project. And I said, okay, let’s bring them home. And when I brought them home and put them together, I immediately saw three octagons…it looked like three octagon end tables. And I thought, oh, this is a brilliant future project, and I should submit it to Nocturne…because the messages were created by the people, and it was done at another Art at Night festival. So, I submitted it to a different Art at Night festival…and they loved the history, that it came from Antigonight. They just loved it. And so, one of the things I wanted to do was take each light box and have a sensor put in. And so, whenever anybody walks by it’ll light up. The company that created my permanent, large-scale light boxes for the Antigonight performance is making them now for Nocturne. Eureka Technologies. There’s 18 altogether, so it’s going to be quite a light show.

B O D Y: Can they be put into different formations the way the small paper light boxes could?

Michelle Sylliboy: Oh yeah. Because they’re going to be wireless. They’re going to have a sensor with L E D lights. And they’re going to put an imprint of the earth on top because the language comes from the land. My elder told me that the language comes from the land because it was used as maps. And so, if you get close to the light box, you will see an image of planet earth. And so, the connection fits. And then on the side, you’ll see the meaning of the Komqwejwi’kasikl.

B O D Y: Wow, okay.

Michelle Sylliboy: When I was telling the guy at Eureka, I said, you know, the language comes from the land and he goes, well, why don’t we put a map of the earth and then cut out the language. And I said, that’s brilliant. <laugh>

B O D Y: I’m interested in this idea of collaboration and your idea of Nm’ultes (see you later) that you’ve talked about previously as a guiding philosophy. Are they connected for you?

Michelle Sylliboy: Well, I think the light boxes have that philosophy attached to it because when I wrote my paper about Nm’ultes it was in the early part of my research because I wasn’t sure what to do with my whole dissertation. I thought about what happened to me in 1988, when it all began, and how every five years I would pick up the research about the language and then I would put it away, and then I would pick it up. I remember thinking I should call it my Nm’ultes theory or philosophy because I would literally just put it aside until I was sure what I wanted to do. And it wasn’t until the PhD came along, that I realized that this is a PhD project, and it’s something that I can do as an artist. Even with the whale bones. When my brother spotted the bones, I couldn’t do anything right away because of the smell of the bones, the dead carcass and everything. So, I had to, you know, put it aside, put aside the Putup – the whale.

B O D Y: Okay.

Michelle Sylliboy: Yes, as you know Nm’ultes means, see you later, whether in person or in spirit, because there’s no word for goodbye in my language. We don’t have a word for it. We’ll say Nm’ultes. And because life has interesting trajectories, we’re all here temporarily, plus, in my culture the spirit world and the living world are no different. We communicate with our ancestors the way I communicate with you now. And so, the idea of putting things aside or saying Nm’ultes…like the whale, I had to put it aside until I was ready. I also had to put aside working around the Komqwejwi’kasikl language until I was ready, until I knew what was meant to happen. And so, when I was ready, I had the idea of creating a living curriculum, with the Komqwejwi’kasikl because it had never been done this way. But as an artist it was more natural for me to create a living curriculum, hence carving the whale bones and painting the Komqwejwi’kasikl onto my photographs of the land. And by saying Nm’ultes, to the light boxes, I put it aside until I knew what to do. I’ll see it later, and now it’s about to be transformed.

B O D Y: Do have more collaborative projects on the horizon?

Michelle Sylliboy: Yes, I’m about to collaborate on two major projects. One is with Serbian opera composer Ana Sokolovic, and the other project is with the director of LAMP who wants me to write a musical.

B O D Y: That’s gonna be amazing.

Michelle Sylliboy: <laugh> Yeah, I have all these fascinating collaborative projects that are about to happen in my future, and all of it is connected to Nm’ultes, allowing me to percolate on the process. Nm’ultes is my philosophical way of working through each artistic project because it’s becoming bigger and more interesting, and it involves collaborating.

B O D Y: Thank you very much.

Michelle Sylliboy: aqq nin welalin (thank you)

— Jessica Mensch

Further Reading:

Artist’s Website

Artist’s Instagram

Live at Obey Convention 2019 | Michelle Sylliboy and Friends | Michelle Sylliboy & Friends (bandcamp.com)

Interview with Writers Federation of Nova Scotia

Projects at Nocturn Nova Scotia